As a youngster I was very good at playing at sight. That’s fun, and essential for anyone who wants to make it on my second instrument, the organ. It also earned Teenage Me a stream of hard cash and some interesting gigs, from weddings and funerals to accompanying musical theatre productions, to playing in a band.

But when it comes to learning difficult music – I knew then and I’ve been reminded now – it means extra demands on ones self-discipline and patience.

Because it’s too easy, with the score in front of you, always to be reading the notes, rather than committing them to memory so that you can focus on the musical and physical aspects. (And it’s too easy to kid your teacher that you practised more than you really did.)

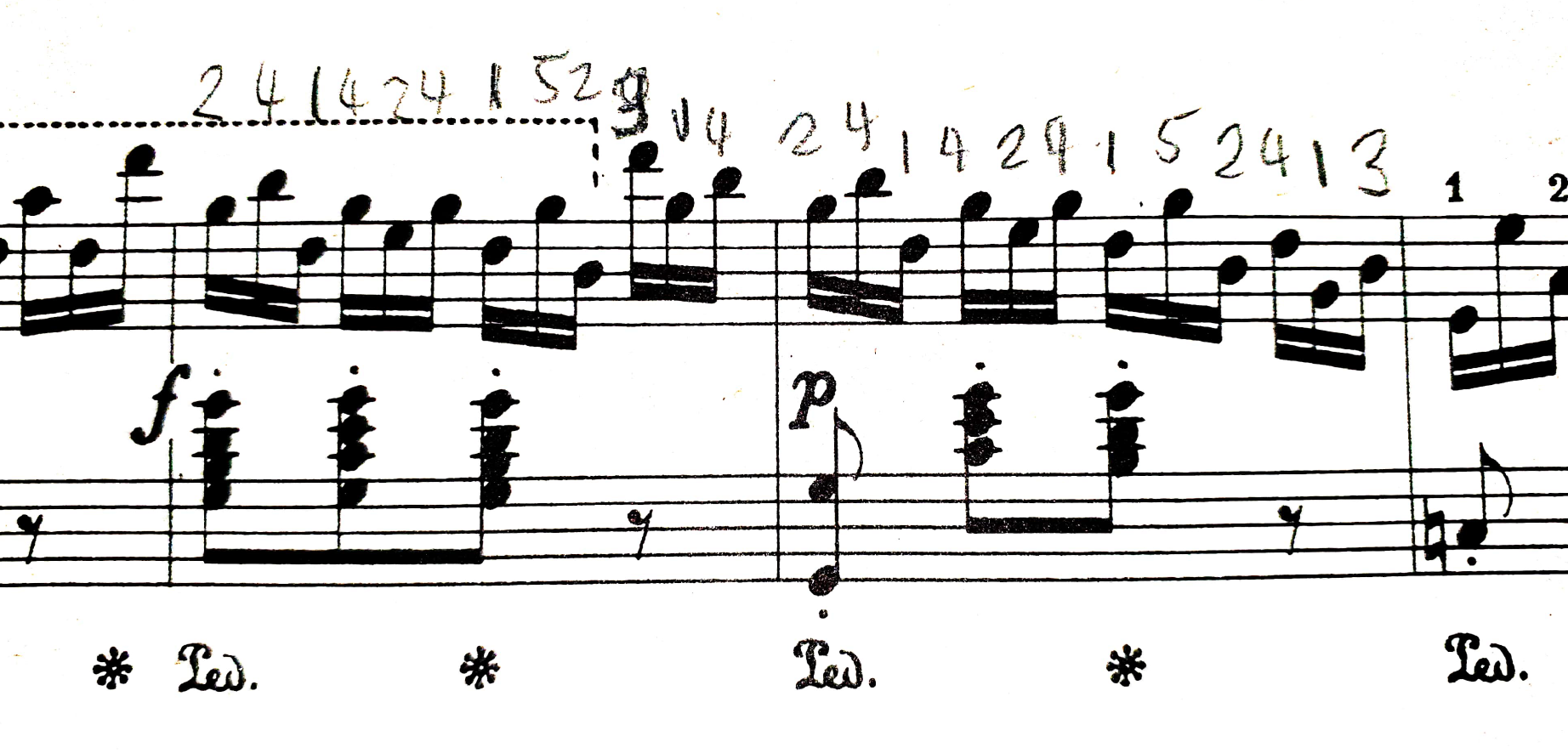

It’s especially true of fingering. The golden rule, which I never really kept to, is that you choose a fingering near the beginning of the process, and stick to it. (Unless you’re a genius like Krystian Zimerman, who learns 3 different fingerings – note, learns – for everything.) You simply can’t be in the music, and the notes can’t be in your muscle memory, if you are making real-time decisions, however instinctive, about which finger to use.

The late Sviatoslav Richter, one of the greatest pianists of all time, is well known for playing with the score in front of him, but there’s a story behind that. Namely that he lost his way once when playing from memory, and that caused him ongoing anxiety that was allayed by having the pages there. It’s not that he didn’t know the piece inside out. He did.

So a lot of marking up of scores will be going on this week. And I’ll be making a conscious effort not to look at the page so often.